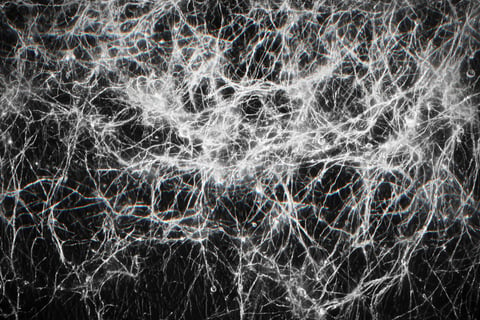

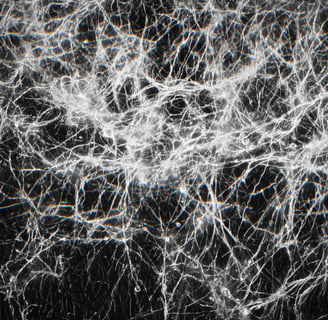

A living network

We see here how trees, fungi and bactéria cooperate and form a very usefull network.

Lambert van Dinteren

2/10/20245 min read

Live 'in relationship'

For many of us, trees are obvious. They are found in the gardens and parks of the city, they form the woods and forests, but it stops there. We admire their aesthetics, we are grateful for their shadow, we know that we must respect them for their action on CO2 and their supply of oxygen, but that’s all.

A small minority «embraces» the trees. On the internet there is an offer of sylvotherapy. There are also those who follow a «tree zodiac»[1] to establish their horoscope or who live with «the Celtic year of the trees». But this is an exception and it is not always clear what it corresponds to[2].

So it is relevant to first ask the basic questions: What is a tree? How does a tree live? What is its role in the ecosystem?

The tree is by excellence a species that lives ‘in a network’ [3].

The tree ‘is’ itself network:

It is a set of roots, bark, wood, branches, buds and/or leaves; each part plays a role for the whole and is served by the whole

The tree has a set of organs; leaf stomata, root hairs, xylem

It is made of osmosis, root pressure, capillarity, foliar aspiration, transpiration, diffusion to allow the sap to rise and fall and thus serve all the elements that make up the tree; water, sugars and carbon or chemical repellents

The tree also ‘lives’ in a network :

The tree is part of an ecosystem that allows thousands of other species (plant and animal, fungal, bacterial, viral) to live

Thus, there are animals that nest in the branches of the tree (cute troglodyte, chickadee, magpie, etc.), others that dig a hole in the trunk (woodpecker) or use the holes of others (squirrel, pigeon, bat). There are others, small, that use cracks in the bark to shelter (spiders). There are animals that find fruit (acorns, faines, apples, etc.) in and under the tree, insects in its bark or in the humus at its feet, lichens to graze on its bark or sap to suck underneath. The tree thus represents the 'house' and 'canteen' of these animals.

The tree also plays a role in enriching the soil, especially when in the fall it drops its leaves. All the richness of nitrogen and carbon (among other elements) returns to the earth and will form humus. This return to earth is not done alone; A whole battery of microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, myriapods, nematodes, springtails, fungi, earthworms, crustaceans, gastropods) is necessary for this transformation. And so many species live on it. By the way (while eating), lumberjacks tirelessly pierce the humus, which allows oxygen, which most of the organisms that live there need, to circulate.

These microorganisms are then serve as food for beetles, predatory spiders, moles or birds. The same that in turn serve larger birds, foxes and other predators. A whole food chain develops and maintains itself there.

The tree is a key agent in the Earth ecosystem; it diffuses oxygen in the air, it captures CO2 and stores it in the biomass at its feet

It is the partner of other trees in the ecosystem of a forest with which it exchanges carbon, nitrogen, antibiotics and information

It would take more time to explain all this, we will do it in another post, but basically, the tree is linked with other trees via the mycelium. The mycelium-filaments in the soil, carries food, phytosanitary molecules and messages. And it takes advantage of the situation to take a part of the sugars transported for itself (the fungus that does not have chlorophylls cannot “make” sugars).

It is a privileged partner of the mycelium, as we have briefly seen, to which it provides sugars while the mycelium provides trace elements as well as substances that strengthen immunity.

This is where the term 'network' is most eloquent, since in the soil there is a very important set of roots and rootlets as well as hyphae (the filaments of fungi), which cross and intersect and communicate in all directions.

As a result :

The tree cut off from its network is struggling to survive; it is more regularly lacking water or nutrients or ‘medicines’. It is also lacking the warnings of approaching insects that attack trees.

And the other members of the network disappear in the absence of trees (when there is no more humus formed by its leaves, when there is no more place to nest, when there are no more leaves to devour, insects to peck in the cracks of the bark …).

If we 'think' our society, this 'networked' life could be a very powerful model. Like plants and fungi, we know that ‘living alone’ makes us more fragile. Humanity has precisely “created society” to be stronger together. And in the face of great threats as we live today, living in society, in network is more necessary than ever.

What is interesting with mycorhyme networks (from ancient Greek: múkēs = mushroom and rhíza = root):

They are acephalic (from ancient Greek: akhephalos – a = without kephalê = head) – it is a network ‘without head’, without chief

The network intersects and intersects again, so the information or resource can go in all directions – there is no linear process, which allows for detours when blocked, which also allows for new (unplanned) connections and so a lot of creativity, ….

The network can go very far (a mycelar network can reach 9km) to look for resources – which makes it possible to fill significant gaps.

These are all elements of a political philosophy. We will talk about them again. For now, we can recommend that you read Merlin Sheldrake’s book, 'Entangled life' .

Perhaps one more thing; if we see how many animals find their living space in and under the tree, we see a how nature knows how to 'make room for the other'. Yet another element that would be to take up in a philosophy that thinks of society. We will do it in another post.

[1] For example : La sylvothérapie - Les bienfaits de la sylvothérapie - Auprès de mon arbre (aupresdemonarbre.org)

Le Zodiaque des Arbres, Didier Colin, Eds. Edition1, 2004

[2] ‘De quelles preuves scientifiques disposons nous concernant les effets des forêts et des arbres sur la santé et le bien-être humains ?’, Kjell Nilsson et al., dans Santé Publique 2019 / HS1 (S1), pages 219 à 240

[3] We base on:

‘La Vie Secrète des Arbres. Ce qu’ils ressentent. Comment ils communiquent’ (Peter Wohlleben (2015))- Peter Wohlleben est un forestier allemand, actuellement en charge d’une forêt écologique. Wohlleben fait un état des recherches actuelles et les lie à son expérience de forestier.

‘Être un Chêne. Sous l’écorce de Quercus’ (Laurent Tillon (2021)) - Laurent Tillon est un français, biologiste et ingénieur forestier à l’Office National des Forêts. Dans ce livre, Tillon suit un chêne, en lui donnant la parole, sur deux siècles en France de Henri IV à nos jours, et montre aussi bien la vie de l’arbre que ses interactions avec son habitat et les influences des évolutions dans la société sur les arbres.

‘A la recherche de l’arbre-mère. Découvrir la sagesse de la forêt’ (Suzanne Simard (2021)).- Suzanne Simard, chercheuse en écologie forestière à l’Université de Colombie-Brittanique (Canada), raconte en forme autobiographique ses découvertes sur la vie des arbres.

‘Le monde caché. Comment les champignons façonnent notre monde et influencent nos vies’ (Merlin Sheldrake (2021)).- Nous avons déjà vu ce livre dans le chapitre précédent.

‘Les écosystèmes’, dans ‘Livret sur l’environnement 2020’ (Institut de France, Académie des Sciences) (Henri Décamps (2020)) - On l’a déjà vu plus haut.

‘Le pouvoir caché des arbres’ (Thierry Beaufort (2020)).- Il s’agit là d’un livre pour la découverte des arbres en famille. On en trouve d’autres dans les librairies ou les bibliothèques.